When Everything is Better Than Dollars

The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly of Index Investing

Part I: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The Good

It’s 2025. Most people still think stock investing is difficult and risky, a gamble where only the quickest draw wins. But in reality it’s the opposite—it’s a solved problem.

It was solved by John Bogle in 1976, when he launched the first market cap-weighted index fund. He realised that most investors couldn’t beat the market, and the fees they paid trying were destroying their returns. His solution was elegant—stop trying. Just own everything in proportion to its market value, pay almost nothing in fees, and capture the market’s return.

Wall Street ridiculed it as “un-American” and “a sure path to mediocrity.” The fund raised only $11 million against expectations of $150 million.

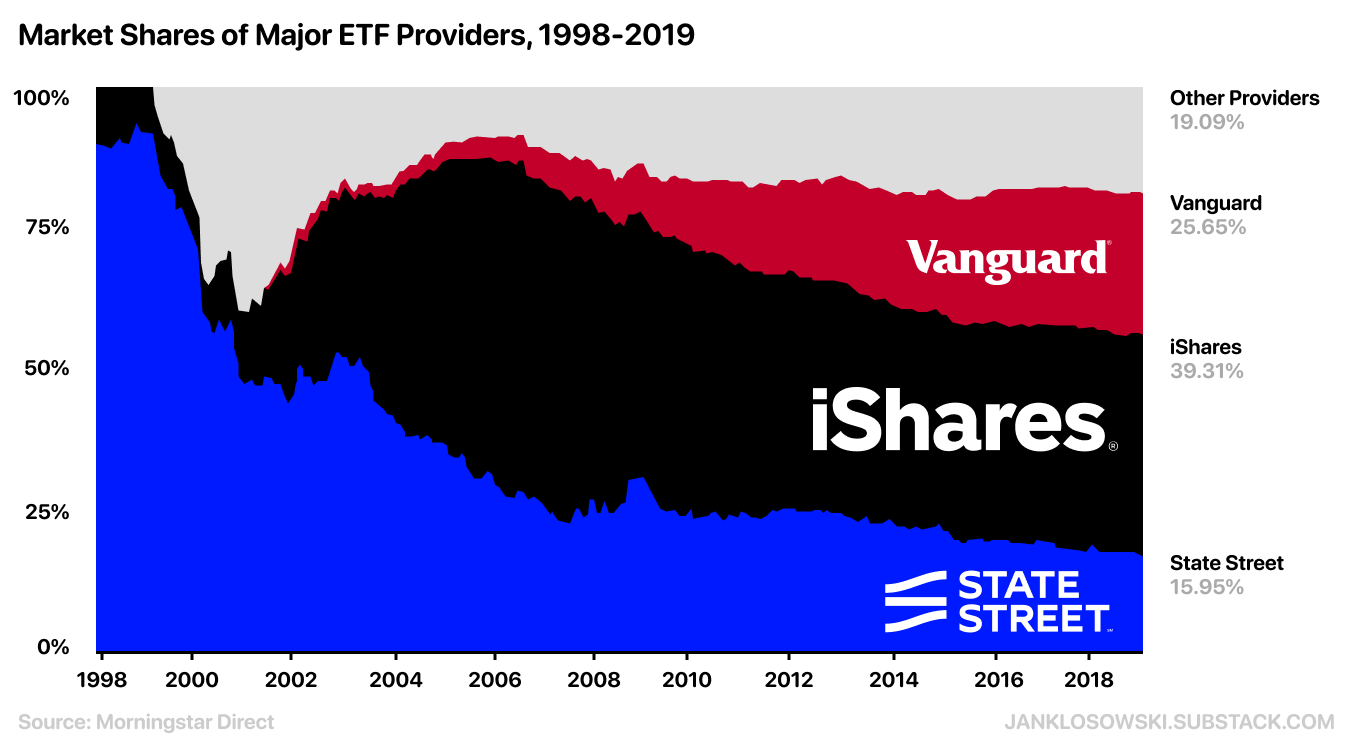

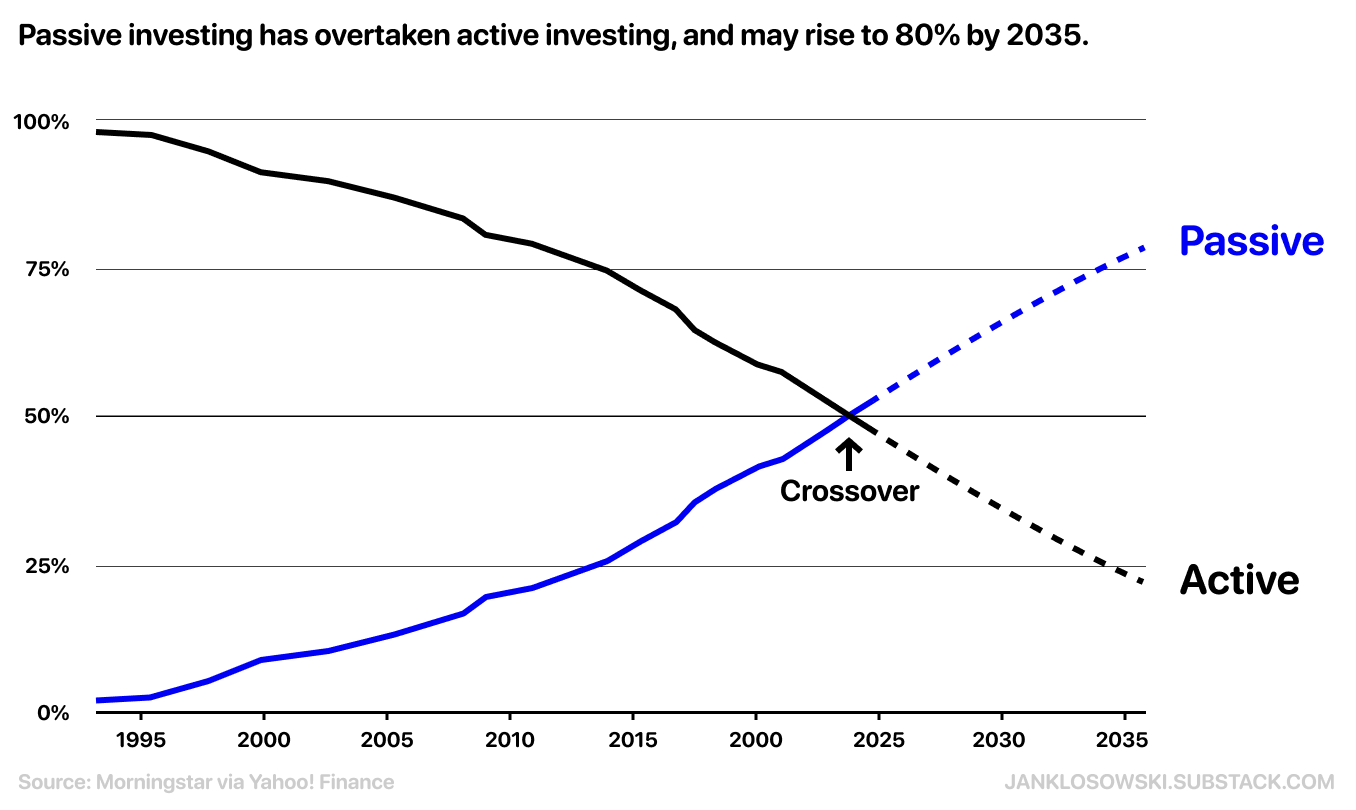

But Bogle was right. By 2000, his Vanguard 500 had surpassed the legendary Magellan Fund. Today, market cap-weighted index funds control roughly $13 trillion in U.S. equities alone—nearly half of all long-term mutual fund and ETF assets.

So, just dollar-cost average into a broad market index fund, and that’s it. That’s the solution. Can you do better than this? Maybe. Most people can’t.

The good news is; if you just do that, you’ll double your money every 7 years or sooner.

*

But the scale changes everything. Index funds were designed to be price takers—passive participants riding the wave of market returns. But when they’re the biggest shareholders in nearly every company, they’re inevitably price makers, influencing corporate governance, capital allocation, and market dynamics in ways Bogle never imagined.

The question is not whether index investing works for individuals—it clearly does—do it. But what happens when the solution becomes the system?

The Bad

In 2025, Tesla shareholders voted on Elon Musk’s $1 trillion compensation package—the largest in corporate history. If Tesla hit an $8.5 trillion valuation and twelve operational milestones, Musk would receive stock worth up to a trillion dollars.

Proxy advisory firms like ISS urged a “no” vote. They said the package was excessive, lacked guardrails, dangerous.

But here’s where it gets interesting: who are the biggest Tesla shareholders? Vanguard, BlackRock, State Street—the index fund giants that collectively own more Tesla stock than anyone except Musk himself.

Representing the actively managed ARK Investment, Cathie Wood had a vastly different opinion:

“Isn’t it sad, if not damning, that institutional shareholders rely on proxy firms to tell them how they should vote? Index funds do no fundamental research, yet dominate institutional voting. Index-based investing is a form of socialism. Our investment system is broken.”

She’s not wrong. Index funds own massive stakes in Tesla—not because they believe in the company, but because Tesla is 2.4% of the S&P 500. They have to own it. They’re locked in by their mandate.

Despite having enormous stakes, they simply don’t have skin in the game the way activist investors do. They don’t profit from Tesla specifically succeeding. They track indices, not businesses. Their incentive is to minimize controversy, follow proxy advisors, and avoid standing out.

Let’s make it clearer: The people with the most voting power are institutionally required not to care about company performance.

In the old market, shareholders were gunslingers—they lived or died by their picks. Now, the biggest shareholders are deputies who don’t care which side wins. They’re just counting the bodies.

Eventually, the package was accepted. An active investor, Mike P, who voted ‘yes,’ captured the difference perfectly:

Today, I cheered in my car as it drove me home when I heard that Elon’s pay package was approved. I voted my 750 shares on it with a huge grin on my face. If Elon gets paid 1 trillion dollars, I will be a multimillionaire.

That’s happy ending, but when you zoom out, you see a much bigger problem:

Index funds break price discovery

The efficient market imagined by Eugene Fama and practiced by Benjamin Graham works when investors do research, make bets, and allocate capital to companies they believe will succeed. The best capital allocators study balance sheets, evaluate management, assess competitive advantages—then put their money where their analysis leads them. Winners—those who do the best job—govern most of the capital.

That’s how capital flows to the best companies. That’s how markets separate winners from losers.

But index funds don’t do any of that. They buy Tesla because it’s big. They buy Nvidia because it’s big. They buy Apple because it’s big. Market cap becomes the only metric that matters.

There’s no research. No analysis. No conviction. Just: “It’s in the index, so we buy it.”

We see this clearly when traders frontrun news about companies joining indices—like when Strategy joined the Nasdaq 100, or when it almost joined the S&P 500. It’s hard to avoid conclusion that the announcement itself moves prices, regardless of fundamentals.

When enough capital operates this way, you get a self-reinforcing loop. Big companies get bigger not because they’re performing better, but because they’re already big.

That’s not price discovery. That’s price following.

Everything is a Memecoin

The new generation of investors grew up on memecoins. They didn’t have a chance to experience the meaning of fundamentals. Traditional metrics like P/E ratios or free cash flow seem disconnected from results. Many are calling value investing dead.

As Jeff Park writes in The Fall of the Intelligent Investor:

“Benjamin Graham’s definition of value is no longer useful... Investors no longer care about empirical metrics like cash flows because there are greater ‘qualitative’ shocks that can upend the valuation input overnight... The future belongs to the Ideological Investor.”

When the biggest pools of capital are required to ignore fundamentals, and the newest investors never learned them in the first place, and pick stocks based on their memetic potential, what’s left to anchor prices to reality?

Everyone’s digging for gold, but nobody knows what gold looks like anymore.

The Ugly

In 2019, Michael Burry—yes, the guy who saw 2008 coming and made a fortune betting against subprime CDOs—gave an interview to Bloomberg:

“The recent flood of money into index funds has parallels with the pre-2008 bubble in collateralized debt obligations. Central banks have more or less removed price discovery from the credit markets. And now passive investing has removed price discovery from the equity markets.”

His concern wasn’t just about individual companies being mispriced.

“This is very much like the bubble in synthetic asset-backed CDOs before the Great Financial Crisis. Price-setting in that market was not done by fundamental security-level analysis, but by massive capital flows based on Nobel-approved models of risk that proved to be untrue.”

Burry pointed out something most people miss about index funds:

Liquidity Is an Illusion

“The dirty secret of passive index funds is the distribution of daily dollar value traded among the securities within the indexes they mimic.”

Trillions of dollars are tied to stocks that barely trade. The S&P 500 sounds like the most liquid market in the world, but over half the companies in it trade less than $150 million per day. That sounds like a lot until you realize trillions of dollars are indexed to them.

Right now, money flows in smoothly because index funds are buying a little bit of everything, all the time. But what happens when everyone wants to sell at once? Who’s on the other side of that trade?

There won’t be enough buyers. The same mechanism that made it easy to pile in—automatic, mindless capital flows—will make it catastrophic to get out.

Index fund investors are more often buy-and-hold types, but even if binding 500 stocks into one basket does not increase volatility, it does increase correlation (everything moving together), which means when there’s a crash, it affects everything simultaneously. That’s a form of the increased systemic risk Burry saw before.

In 2008, everyone thought they could sell their CDOs whenever they wanted.

Then one day, there were no buyers.

“This fundamental concept is the same one that resulted in the market meltdowns in 2008,” he said.

The correlation problem goes beyond index funds: stocks, bonds, crypto, gold, and real estate that historically provided diversification now rise and fall in unison. It’s a flight to assets, any assets, as capital seeks refuge from monetary debasement.

Here’s what Burry couldn’t quite say—or maybe didn’t see.

The index fund bubble isn’t just a market problem. It’s a monetary problem.

When Market Becomes a Saving Account

In November 2025, China’s central bank resumed bond purchases—effectively printing money—and Bloomberg reported “fund rotation into equities.” This isn’t theory: central banks are actively forcing capital into stocks regardless of valuations.

Why? Because people can’t hold cash. Inflation erodes it. Bonds barely keep up. Real estate requires capital most people don’t have. Gold doesn’t yield anything.

Everyone is forced into stocks—not because they’ve analyzed companies, but because there’s nowhere else to go. The stock market has become the new savings account. Index funds are simply the most efficient way to use it as one.

A Thousand Year Old Problem

In Debt: The First 5,000 Years, David Graeber discusses an Islamic philosopher Al-Ghazali and his idea that ideal money should be abstract—its monetary function shouldn’t compete with any other utility. That’s an interesting observation from the era of commodity money:

When gold serves as money, its monetary demand competes with its use in jewelry and industry.

This applies to index investing perfectly:

When stocks serve as money, their monetary demand—as inflation hedges and stores of value—competes with their primary function: allocating capital to productive enterprises.

The result is price distortion in both.

This is the real “ugly” of index investing: it’s a symptom of monetary dysfunction. When fiat currency fails as a store of value, every asset class is forced to absorb that monetary premium and serve dual, competing purposes.

When that happens, neither function works properly.

The current system is broken. Fiat currency forces everyone into asset markets. Index funds are the rational response, but they’re breaking price discovery and creating systemic fragility.

Part II: For a Few Dollars More

For decades, everyone’s been chasing paper dollars—stocks, bonds, real estate—anything but dollars themselves. But what if the problem isn’t what you’re chasing? What if it’s the dollars?

Equation of Exchange

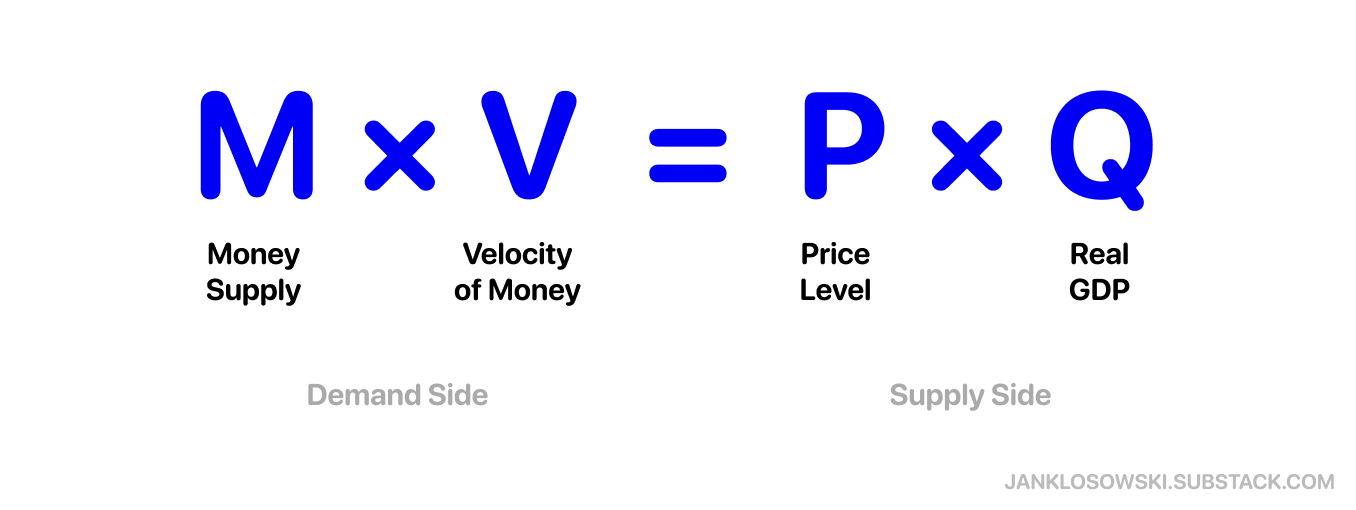

In 1911, economist Irving Fisher formulated what he called the Equation of Exchange:

Where M is the money supply, V is velocity (how fast money circulates), P is the price level, and Q is real GDP (the quantity of goods and services produced).

Simplified, it means: Total Money = Total Value of Goods & Services

Here’s why this matters: If the money supply (M) grows faster than economy produces goods and services (Q), then prices (P) rise and we get inflation. Currently, it does and we do.

However, if we could have money that doesn’t grow supply, the opposite would happen: prices would fall, and the purchasing power of your money would increase automatically with economic growth.

As the economy grows, your money automatically captures that growth because the same money now represents more productive capacity.

You don’t need an index fund. The money itself is the index.

In Search of The Hardest Money

But this only works if the money supply can’t be inflated.

For most of human history, that was impossible to guarantee. Gold was the closest, with the lowest stock-to-flow ratio, but the supply was still growing and in the digital economy the form factor feels like an ancient relic making it hard to consider money in a traditional sense.

Then came debt-based fiat currency, with supply expanding indefinitely. Every year, more dollars, more euros, more yen. We all know this part:

Despite the goods and services side growth constantly accelerating, the money side always grows faster. As we discussed, to maintain your purchasing power you’re forced to convert it into something else: stocks, gold, real estate, anything that might keep pace with monetary expansion.

Index funds become the default solution—a way to keep your purchasing power tied to economic growth. We discussed all the problems that arise with it.

But what if money could do its job again?

As we already noticed, we would need money with a finite supply, and we know one.

Bitcoin is not only the first form of money with a supply that truly cannot be inflated. There will only ever be 21 million bitcoin. No central bank can print more. In this model, Bitcoin’s fixed supply can absorb unlimited growth in the goods and services of the global economy.

Hyperbitcoinization: The Bitcoin Endgame

The hyperbitcoinization scenario is not about the present, but a hypothetical future.

If Bitcoin becomes the global store of value—what bitcoiners call “hyperbitcoinization”—the equation balances naturally:

M: 21 million bitcoin (fixed)

Q: All goods and services (growing)

Result: Each bitcoin’s purchasing power grows with the economy, accelerated by the gradual loss of coins and other factors decreasing the circulating supply.

Your bitcoin holdings would automatically capture global economic growth without you needing to own stocks, real estate, or anything else as a monetary hedge.

The money itself becomes your “index fund” for human productivity.

Right now, Bitcoin is still in its monetization phase. Its price is driven mostly by new capital flowing in—people discovering it, institutions allocating to it, countries adding it to reserves. It’s volatile. It’s growing through adoption, not through representing economic output.

This is expected. Gold went through the same process over centuries.

But imagine a future where Bitcoin’s adoption has saturated. This is the part skeptics miss when they call it a “ponzi”:

Even without new money inflow, Bitcoin’s growth rate would be driven by the real economic growth rate, because the equation of exchange demands it.

When Money Works

If Bitcoin becomes the dominant store of value, as Al-Ghazali’s ideal abstract money, it could change how the market functions:

Stocks could be just stocks again. No more “I need to be invested in something.” Graham’s intelligent investor could come back from retirement, and active capital allocators could practice true price discovery again.

Real estate would just be housing. Prices would reflect utility—location, quality, livability—not a forced monetary premium.

Gold could become just jewelry. Impossible? For thousands of years, shells were currency. Technology disrupted shells, and it can disrupt gold as well.

The radical idea:

You wouldn’t need to invest to preserve wealth. You could just save. Your money would naturally increase its purchasing power through economic growth.

This future is not guaranteed, but here’s what is certain:

The current system is broken. Fiat currency forces everyone into asset markets. Index funds are the rational response, but they’re breaking price discovery and creating systemic fragility. The solution isn’t to stop using index funds—it’s to fix the money.

The principle is clear: the harder the money, the better markets function.

In 1976, John Bogle fixed investing for individuals. He couldn’t fix the money.

It’s time to fix the money.

Fix the money, fix the world.

Really good read Jan thank you

Good stuff!